The Urban Heat Island

Heatwaves, or extended periods of hot weather, are among the deadliest forms of climate hazard. Compounded with the urban heat island effect–the tendency for cities to be hotter than rural areas because of urban development and industrialization—rising global temperatures put urbanites at a unique risk.

Heatwaves, or extended periods of hot weather, are among the deadliest forms of climate hazard. Compounded with the urban heat island effect–the tendency for cities to be hotter than rural areas because of urban development and industrialization—rising global temperatures put urbanites at a unique risk.

With growing urban populations, extreme heat has implications on cities’ economic vitality, livability, and health. However, in the most vulnerable areas, an accurate assessment of local air temperature data does not exist.

Understanding variation within the urban heatisland has important implications for city planning, disaster management and public health spheres by creating opportunities for more targeted interventions. Hopefully, these can help us reduce the effects of heat exposure now and in a warmer climate.

Baltimore

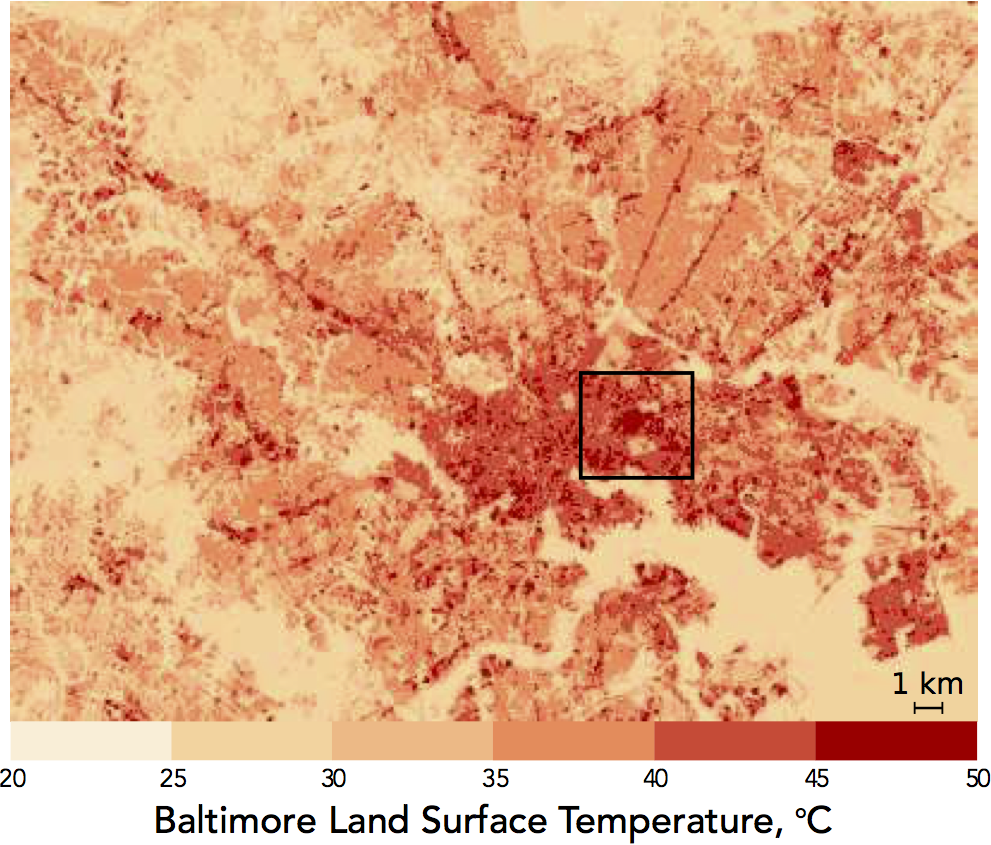

In Baltimore, the City is actively implementing UHI mitigation measures such as cool roofs and tree planting in low income target neighborhoods in East Baltimore. These neighborhoods are characterized by extremely low tree density, few green spaces, high percent impervious cover, and—according to thermal satellite imagery—particularly high land surface temperatures relative to other parts of the city. Since summer 2014, we have deployed a summertime thermometer network in the city. Our results show that mean minimum daily air temperatures in East Baltimore do not differ significantly from the station.

More important are the differences between land cover type, with sites surrounded by impervious surfaces being warmer than sites surrounded by low vegetation by about a degree Celsius (approximately 2 degrees F). Trees were also not found to affect temperature at the tree canopy density found in East Baltimore.

Nairobi

Nairobi, Kenya exhibits a wide variety of microclimates brought about by heterogeneous surfaces, from paved roads and high-rise buildings interspersed with low vegetation in the central business district, to large neighborhoods of informal settlements or ‘slums’, characterized by dense, metal housing, little vegetation, and limited access to government services. To investigate how heat exposure differs within Nairobi, we deployed a high density observation network in 2015/2016 to examine summertime temperature and humidity. Temperature, humidity and heat index are found to be warmer than the central weather station in several informal settlements, including Kibera, the largest slum neighborhood in Africa. These changes are related to surface properties, notably vegetation abundance.

Resources

- The temperature data are available from the Baltimore Office of Sustainability ()*